Sometimes when I have trouble sleeping, I imagine myself climbing out of a vast underground citadel, stairways upon stairways following each other upward in the light of a single candle. I pass doorways heaped with dust and swivelling, gold-rimmed mirrors of the kind that often feature in Zelda puzzles. Reaching the top after many days I halt inside the entrance, listening to birdsong, my toes inches from a bar of sunshine. Then I rewind the daydream and start again. I fantasise that I’m some ancient creature roused from long slumber to right some epic wrong, but in the end, I don’t really need to know what lies out there in the surface world. I’m in it for the suspense and serenity of the climb.

I haven’t played Hades, the current Stygian adventure of choice, but I’ve spent a lot of time in virtual underworlds this year. You don’t have to look hard for a real-life parallel there. Nor do you have to be an ancient Greek adventurer to know that underworlds aren’t just places of death and disease. They are refuges for wayward imaginations, shelters and spawning vats for ideas swiftly killed by the harsh clarity of sunlight, the abrasive fresh air. The games that define 2020 for me understand this.

Edwin’s games of 2020CarrionCreaksFinal Fantasy 7 RemakeIn Other WatersOthercide

In Amanita Design’s Creaks, ordinary objects such as hatstands and drainpipes spring to life in the shadows of a fortress which blends the British Museum with Fallen London. These objects suggest a kind of critical mass of buried history, packed down like fossils (some of them are, in fact, fossils) to the point that they liquefy and transform, bursting into the realm of sentience. Mind you, Amanita’s astonishingly drawn and coloured backdrops always feel like they’re about to jump out at you. Darkness here covers a wide rainbow, from deep, water-damaged purples to scratchy greys and blues scraped away by torchlight. Curious avian dreams lurk behind the gilt of clockwork paintings, some of which prove to be games themselves.

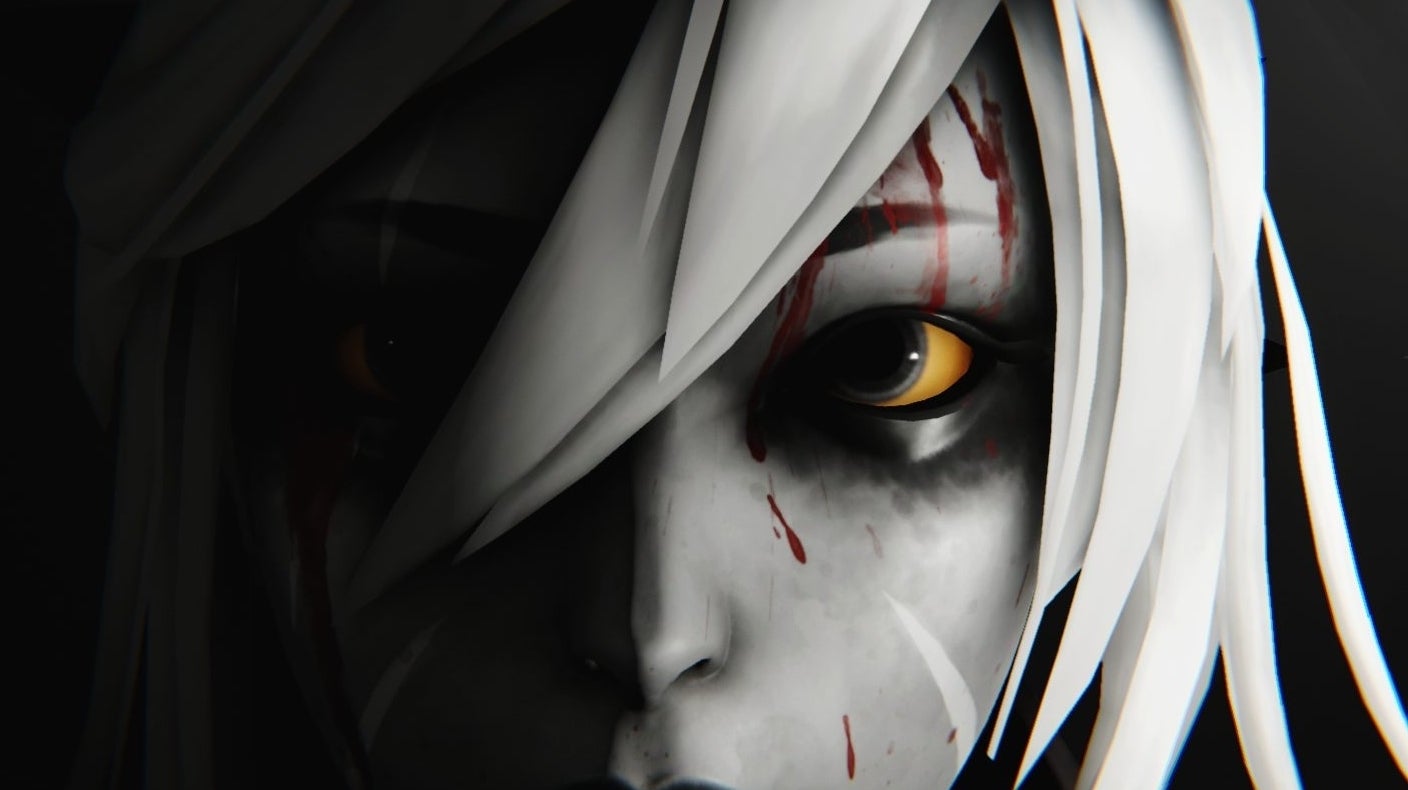

What a difference from the underworld of Othercide, a grid-based mix of Bloodborne and XCOM that has only four colours to its name: blood red, inky black, bone white, eyeball yellow. Othercide’s setting isn’t really a work of geography, though you can read it more literally as chunks of Victorian city floating in the void left by a supernatural cataclysm. Rather, the environment is the interior of a body. Its sky is a thick tangle of dead synapses through which your Daughters – each a clone of history’s greatest warrior – fly like bolts of resuscitative energy. Its mission menu overlooks a sea of amniotic fluid. New recruits are reeled from these midnight waters, pale limbs coiled and hair tapering behind them like an umbilical cord. Old characters you wish to retire are dropped back in, melted down to transferable stats and skills.